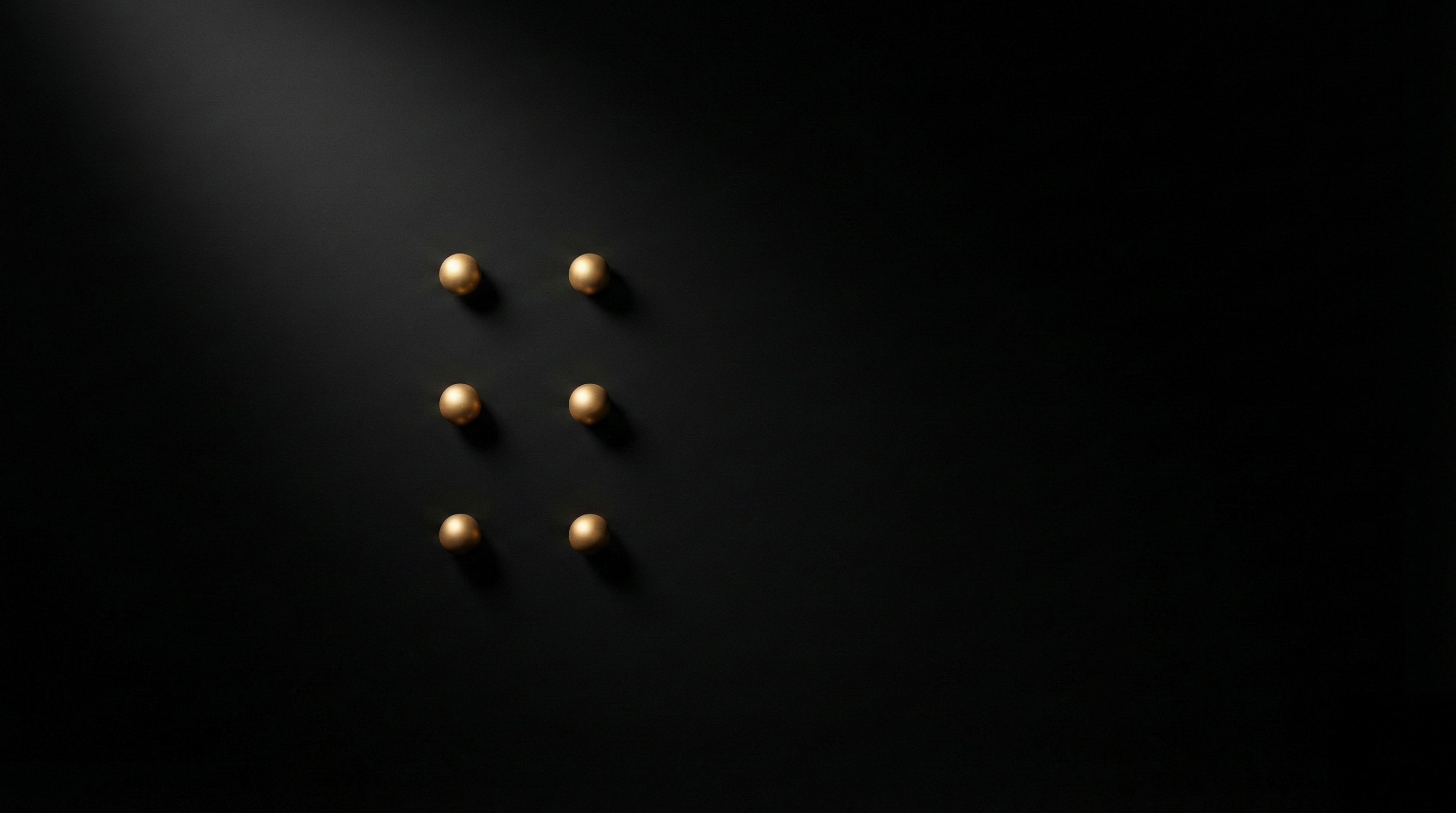

Six dots. Nothing more

Posted on: 4 January 2026

Today is World Braille Day and almost no one will talk about it in terms that aren't patronising. Inclusion, awareness, rights of the visually impaired: fine words, but they miss the point entirely. Braille is not an act of charity towards those who cannot see. It is one of the most elegant communication systems ever conceived by human beings. And its history tells us something important about how communication that lasts actually works.

We live in an age where everyone is shouting. The digital feed is a wall of content, each piece scrambling over the next to capture three seconds of our attention. Brands pay fortunes to interrupt whatever we were watching. Content creators turn up the volume, speed up the pace, multiply the cuts. Algorithms reward whoever generates immediate reaction, any reaction, even anger, especially anger. The result is a background noise that increases every year, and within that noise everyone tries to shout a little louder than everyone else. It's an arms race that no one can win, because when everyone shouts, no one is heard.

Then there's Braille. Six raised dots, sixty-four combinations, no colour, no sound, no animation. A system that cannot be read by those who don't know it. A system that doesn't try to please everyone, doesn't chase distracted passers-by, doesn't optimise for any algorithm. It exists for those who seek it, and that's all. It has worked for nearly two hundred years without ever needing an update.

This Sunday in January falls at a strange moment in the calendar. The holidays are over but routine hasn't resumed. It's a suspended day, a limbo between the noise of champagne toasts and the clamour of diaries filling up again. Perhaps it's the right moment to talk about a system designed to work in silence, without bombarding us with notifications, without demanding our constant attention. A system that communicates better than any campaign calibrated for segments and ideal personas, precisely because it doesn't try to communicate with everyone.

Louis Braille was three years old when he lost his sight. It was 1812, and his father was a saddler in Coupvray, a village about forty kilometres from Paris. The boy was playing in the workshop and injured one eye with an awl. The infection spread to the other eye, and within a few months Louis was completely blind. At ten, he entered the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris, where reading was taught using a rudimentary method invented by its founder, Valentin Haüy: letters of the normal alphabet embossed on paper. The system worked poorly. The letters were difficult to distinguish by touch, reading was painfully slow, and above all, blind people could read but not write. It was one-way communication, from above to below, from the sighted to the blind. Sound familiar?

In 1821, something decisive happened. A French army captain named Charles Barbier de la Serre came to the institute with an invention he had developed for military purposes: a night-writing system that allowed soldiers to communicate in the dark without lighting lamps that would reveal their position to the enemy. Barbier called it "sonography" and it was based on raised dots instead of letters. The idea was brilliant but the system was cumbersome: it used twelve dots arranged in a six-by-two grid and encoded sounds instead of letters, which made it complex and unintuitive. Barbier had designed for himself, for his military needs. He had never asked blind people what they actually required.

Braille was twelve when he encountered sonography. He understood immediately that the basic intuition was right but the execution was wrong. He spent the next three years working on a simplified version. He reduced the dots from twelve to six, abandoned phonetic coding to return to the alphabet, and compressed everything into a space that could be perceived with a single touch of the fingertip. At fifteen, he had completed the system. Six dots, sixty-four combinations: enough to represent all the letters of the Latin alphabet, numbers, punctuation, mathematical symbols, musical notes, even chemical formulas. A semantic compression protocol conceived almost two centuries before anyone invented the term.

There's something deeply counterintuitive about this story. We usually think that communicating better means reaching more people, using more channels, producing more content, optimising for more platforms. Braille did the opposite: he designed a system that could only be used by those who knew it, that required learning, that didn't try to simplify itself to please those who didn't want to make the effort. The constraint wasn't a flaw to be corrected: it was the structure that held everything together. And precisely for that reason, it worked.

The paradox is that the most powerful communication systems are almost always the most constrained. Japanese haiku emerge from the constraint of seventeen syllables and produce poetry that free verse rarely achieves. The Shakespearean sonnet must respect fourteen lines and a predetermined rhyme scheme, and precisely for this reason forces the poet into a precision that free verse doesn't demand. Handwritten love letters, with the constraint of a finite page and the impossibility of deletion, communicate something that no digital message will ever convey. Constraint filters noise and forces the essential.

In contemporary communication, the opposite happens. Every constraint is experienced as a limit to be overcome. More channels, more formats, more frequency, more reach, more views. The result is that brands talk a lot and communicate little. They spend fortunes interrupting people who weren't looking for them, then wonder why those people ignore or despise them. They've removed all constraints and find themselves without structure, without identity, with nothing to distinguish them from the background noise. They shout ever louder in a room where everyone is shouting.

Braille operates on an opposite principle. It doesn't try to get noticed by passers-by: it exists for those who seek it. It doesn't adapt to audience tastes: it requires the audience to adapt to it. It doesn't simplify the message to reach more people: it maintains complexity to better serve the right people. It's communication that presupposes a pact: I offer you something of value, you make the effort to learn how to access it. Those who don't want to make that effort are not my audience, and that's fine.

There's a term that describes systems of this type: antifragile. Not simply robust, meaning capable of withstanding shocks, but systems that become stronger when stressed. Braille has passed through two centuries of communication revolutions without changing one iota. It survived the arrival of the telegraph, radio, telephone, television, computers, smartphones, voice assistants, artificial intelligence. Every time a new technology seemed to make it obsolete, it turned out to still have an irreplaceable role.

In the 1990s, when voice synthesizers began to become accessible, many thought Braille was destined to disappear. Why learn to read with your fingers when a computer can read anything to you aloud? The answer came from the data: blind people literate in Braille had significantly higher employment rates and education levels than those who depended only on voice technology. Reading with your fingers is not the same as listening with your ears. It activates different cognitive circuits, allows a different understanding, builds a different autonomy. The passive message that arrives in your ears is not the same as the message you go looking for with your fingers.

It's a distinction that applies to any form of communication. There's a difference between content that interrupts you and content you go looking for. Between the message that chases you and the one you find because you wanted it. Between communication that shouts to get noticed and communication that whispers knowing that those who need to hear will hear. The first is easier to measure, generates impressive numbers, fills reports. The second is harder to quantify but builds something the first never will: a bond with people who chose to be there.

In a few months, UNESCO is expected to recognise Braille as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The nomination was led by Spain with support from France, Germany and other European countries. It's an appropriate recognition. Not because Braille is a relic to protect, a fossil to put in a museum alongside typewriters and rotary phones. But because it represents something we risk forgetting: you can communicate powerfully without shouting, without chasing, without trying to please everyone.

There are approximately 285 million people with visual disabilities worldwide. Of these, 39 million are completely blind. In the UK, we're talking about nearly two million people with serious visual impairment. For all of them, Braille is not a nostalgic accessory: it's basic cognitive infrastructure. It's the system that allows them to read medication instructions, lift buttons, restaurant menus, station signs. It's the difference between always depending on someone else and being able to manage alone. It's communication that creates autonomy instead of dependence.

Braille died at forty-three, probably from tuberculosis, on 6 January 1852. Two days after his birthday, which is why World Day falls on 4 January. During his lifetime, he had to fight against the scepticism of the sighted people who ran the institute where he taught. The director feared that students would use that code to exchange secret messages he couldn't control. It's a detail that says a lot about the nature of power and the resistance that every truly effective communication system encounters. Those who control existing channels are always afraid of new ones, especially when the new channels give voice to those who didn't have one before.

Today is Sunday. Cities are still half-empty, shops closed, streets quiet. It's the last day of limbo before everything starts again. Tomorrow the noise returns, the notifications return, the feed full of people shouting to get noticed returns. New Year's resolutions are still intact, reality hasn't tested them yet.

Perhaps it's the right day to remember that another way of communicating exists. That you don't need to shout louder than others to be heard. That constraints aren't always enemies to defeat but sometimes structures to build upon. That six dots arranged the right way, read by those who know how to read them, can contain the entire alphabet, all of mathematics, all of music.

Louis Braille designed a communication system that worked, and still works. Without ever chasing anyone, without ever shouting, without ever trying to please everyone. That's more than can be said for most of what we communicate today.